The Introversion Bubble

Recently, I attended a conference alone.

When it came to the conference’s opening night cocktail hour, I was a bit nervous. I knew none of the attendees, and nobody wants to be the person standing alone at a party, fiddling around on their phone pretending to answer email. After exploring the hotel lobby, I dutifully made the rounds, introducing myself to folks at the bar, folks in mid-conversation around the space, and people catching fresh air outside.

Tired, I sat down at a nearby table. Seated there were three women, ten to fifteen years older than me.

“Do you mind if I sit here?” I asked.

“Sure, no problem,” one of them said. The women were engaged in small talk, and they didn’t seem to know each other earlier. Perfect. A chance for some bonding with my fellow loners.

“Hi, I’m Sean,” I said extending my hand.

“Hi, I’m Leslie, and I’m an introvert,” she said.

***

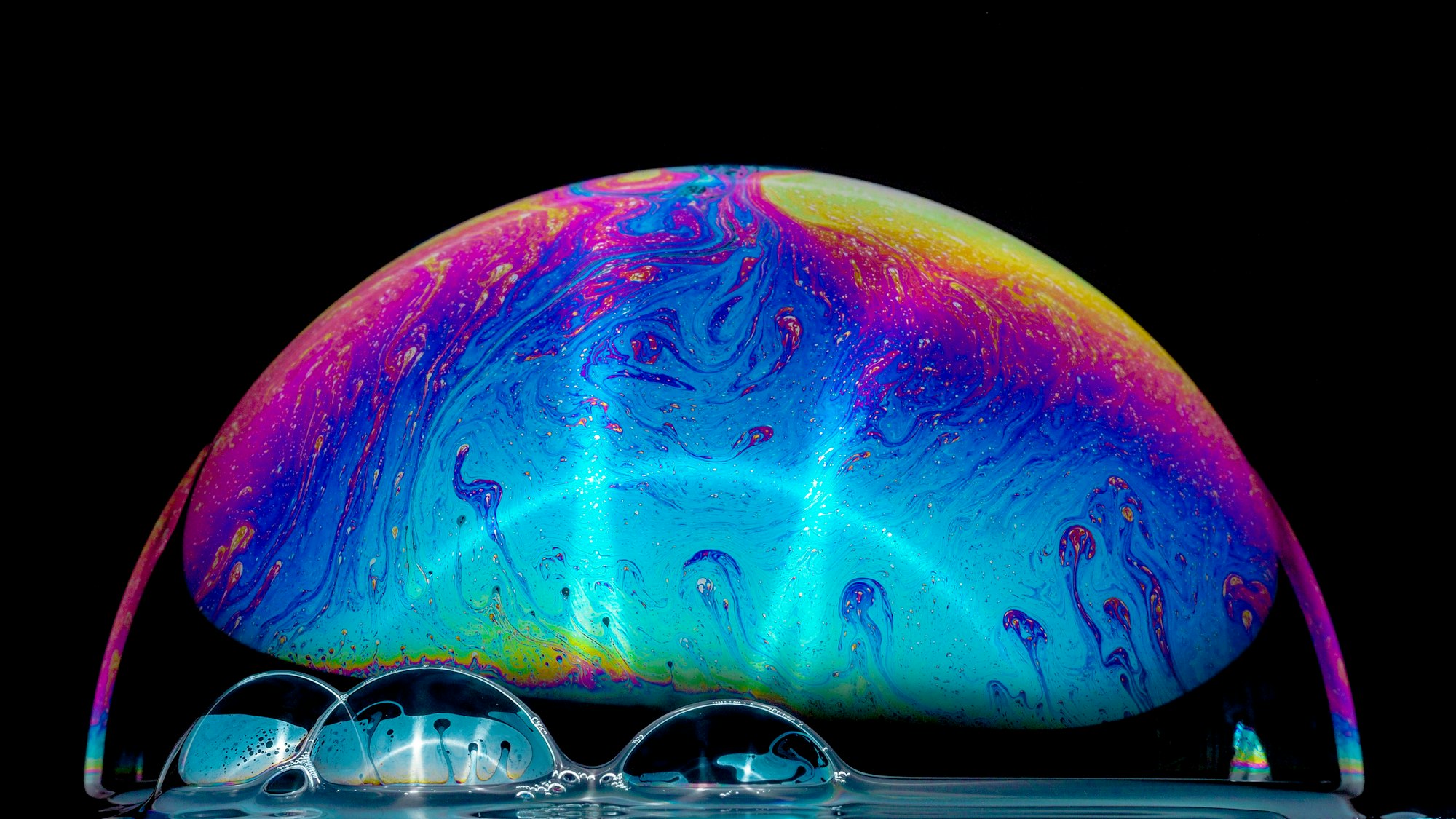

The concept of identifying myself to strangers according to some personality test is unusual to me. But since that interaction I’ve noticed that it’s starting to become socially appropriate to identify ourselves according to the church of Myers-Briggs. Google Trends (above) shows that mentions of the word “introvert” in news headlines is steadily climbing, even reaching “peak popularity” a few times.

In the past year I’ve seen introvert quizzes, self-righteous blog posts, columnists riffing on introversion, and several books asserting that, goshdarnit, introverts can contribute. Introversion is becoming an entire sub-section of self-help books. This needs to stop for two reasons:

1. It is often a misuse of the word “introvert.”

Connecting with our fellow humans can be an undoubtedly troubling, frustrating, and often terrifying experience. Most of us have picked up a phone only to hang up, mid-dial. Or have gathered up the courage to speak to a stranger only to chicken out at the last moment.

Yet the Introversion Bubble has allowed some of us to think that, because we sometimes don’t like crowds, we’re all introverts. It is shifting the meaning of the term. Introverts, by definition, don’t get their energy and inspiration from other people. They need to “recharge” alone at times. Extroverts, on the other hand, will feel “drained” if left alone.

This is different from what many people mean when they self-describe as an introvert. The legitimate description of the personality trait is being co-opted by those who are shy or for those who are uneasy of revealing their ideas in public. Which, I imagine, is something like 90 percent of the population.

Suddenly, false “introverts” are banding together in a pity-party of people who are hiding under the term to excuse themselves from taking risks or interacting with others. Human beings are naturally wired to work in short bursts. It’s why we need to take breaks, go on vacation, and vary our daily tasks.

For introverts, a “break” means some quiet time with a book. For extraverts, it may mean lunch with a few friends. This, however, doesn’t mean an introvert can meaningfully claim they “aren’t good” at getting lunch with friends, any more than the extravert can reasonably claim to never have read a book because “it’s hard to sit still for that long.”

2. It stunts personal growth

Empowered with a word that finally gets at what they’ve been feeling all of these years, many introverts simply throw up their hands when asked to do something counter to their nature.

Despite what our natural introvert/extrovert tendencies are, our jobs and lives often require uncomfortable behavior. The lonely extrovert writer and the introverted salesperson alike both have to act in ways that are “unnatural.” The introvert artist may prefer to work alone, but his art career isn’t going anywhere if people never see his work.

Jessica Lahey wrote about a similar approach in The Atlantic. As a teacher, she has struggled to grade introverts fairly with extroverts.

As a teacher, it is my job to teach grammar, vocabulary, and literature, but I must also teach my students how to succeed in the world we live in — a world where most people won’t stop talking. If anything, I feel even more strongly that my introverted students must learn how to self-advocate by communicating with parents, educators, and the world at large.

Doing things that make us uncomfortable is the path to personal growth. Whenever we get that queasy feeling, that sense that we are out of our element, that is when we learn. That is when we step out of the often automatic behaviors of day-to-day life and do something out of the ordinary — something we’ll remember. This goes for extroverts, introverts, and every other marker on the Myers-Briggs scale.

When we blame the world for not accepting our natural inclinations (“but I don’t like to promote myself!”) we can sit quietly and stew about the current working order of the world. Meanwhile the world keeps going, leaving those who refuse to adapt behind.

Sitting on the sidelines because you’re uncomfortable is betraying your growth as a person and your professional ambitions. Letting a personality test help you better understand yourself is reasonable. But it’s cowardly for a Myers-Briggs score to serve as an excuse to not do something because it’s difficult. Instead, we should use our introversion as a means to better understand how to recharge each day. We should use it as a chance to take better care of ourselves and be more aware of our moods. We should never use it as an excuse.

There are no “extraverts” or “introverts” — there are only people who get things done and people who don’t. If you’d like to get better at regaining your lost energy, identifying as introvert or extravert is helpful. But when dealing with others, or learning something new, throwing up your Myers Briggs type as a defense is nothing but an obstruction.

It’s uncomfortable approaching a stranger to express your ideas for the first time. It can make your heart thump and your muscles tighten. The person could reject you. You could look like an idiot.

Do it anyway.