The Dark Matter Influencer

Author, podcaster, and entrepreneur Paul Jarvis spent years building his email newsletter, writing books, and making courses. His career was the dream end state for many of those in the “creative economy.” There was “passive income,” a published book, and a portfolio of diverse revenue streams.

But earlier this year, he did something drastic. He threw it all away. His newsletter that he sent each and every Sunday? Gone. His decade of articles on his blog? Poof. SEO suicide.

His homepage now reads “I used to have a personal brand, and now I don’t.”

Baller.

-

For previous generations, making a living through an audience (i.e. “fame”) was a rarity. You needed something compelling to share and you needed to get the approval of gatekeeper before even playing the game. 15 years after Web 2.0, however, and the tools for audience building have been fully democratized and socialized. Building an audience is now the default state of operating online. Just ask any tween, they all want to become internet celebrities.

In 2019, Ypulse asked different generations to name their favorite famous person. The results:

The youngest Gen Z consumers were most likely to name an online celebrity as their favorite famous person, while older Millennials were most likely to name a Hollywood celebrity.

But there is a price to pay for these tiny empires. One needs to amass an audience for them to work. That audience must be served. That audience must be responded to and considered. And that audience doesn’t always pay. In fact, they usually don’t.

Fame, followers, and attention are means to an end, and too often they are treated as the end. In the United States of America, the real means to freedom (for better or worse) is money and power. And fame /= money and power. This is why the internet famous still wait tables.

An entire American generation is about to spend their teens and early 20s trying to build an audience only to discover it’s near-impossible to turn that into something financially meaningful. Li Jen writes about this lack of a “middle class” in this kind of creative economy:

On Patreon, only 2% of creators made the federal minimum wage of $1,160 per month in 2017. On Spotify, artists need 3.5 million streams per year to achieve the annual earnings for a full-time minimum-wage worker of $15,080, a fact that drives most musicians to supplement their earnings with touring and merchandise. In contrast, in America in 2016, 52% of adults lived in middle income households, with incomes ranging from $48,500 to $145,500.

While it’s fun to read and think about all of the new platforms and voices in the world, the smart ones are avoiding that game all together.

I posit that there is a deceptively large (and growing) quiet class of king maker. This group prizes anonymity and moving under the radar as they accumulate money and power. They are like dark matter, a powerful force in our universe and culture that we have trouble seeing, especially if we don’t know where to look.

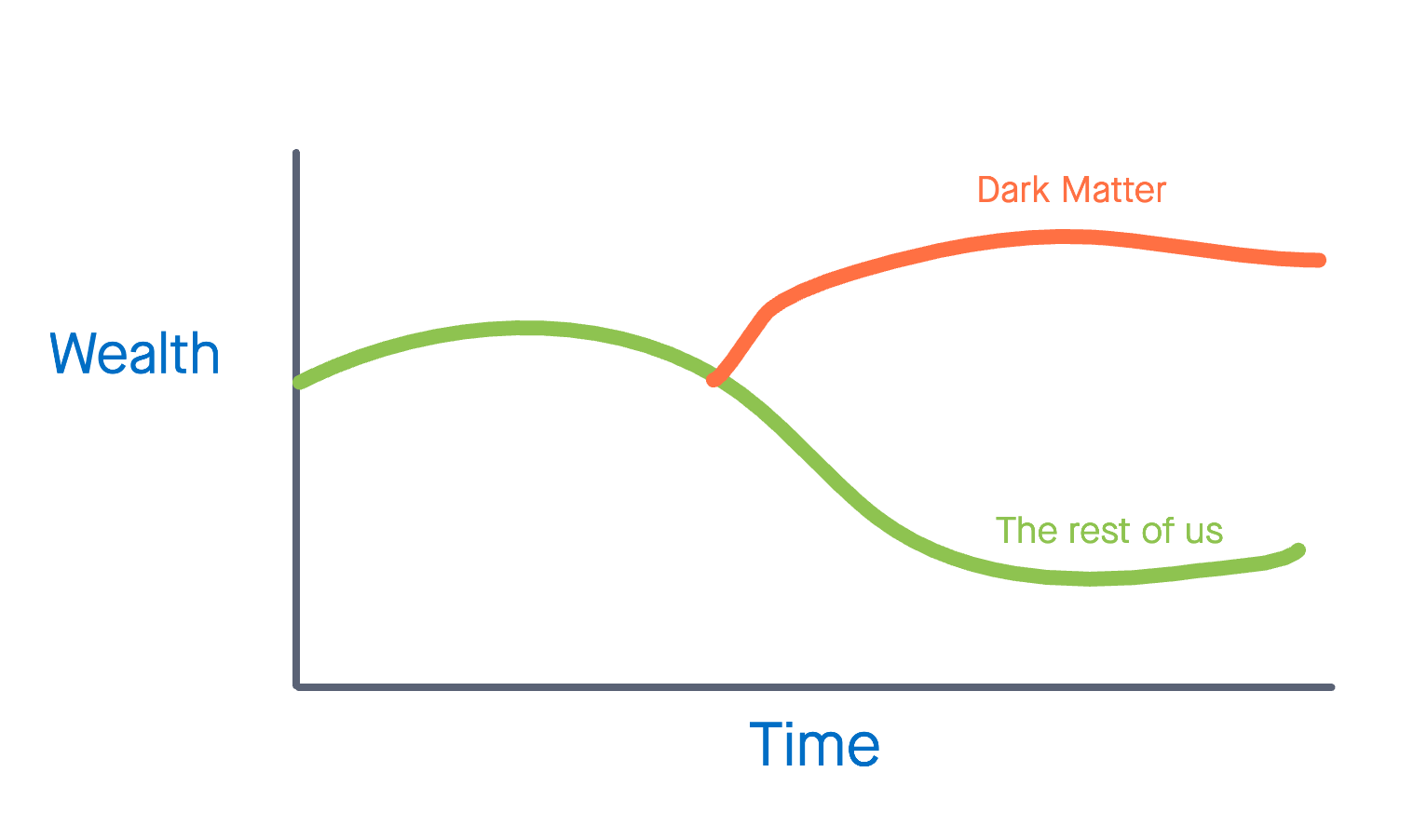

In our COVID “K-shaped” recovery they are on the top side of the “K.” They are accumulating wealth and status and power and staying away from social media or building audiences. They are the producers. They are the editors. They are the funders. They are the silent partners. They are the ones taking advantage (fair or unfair) of some edge they’ve observed in the market and shutting up about it.

To the Dark Matter Influencer, attention is a liability. Attention gets you called out or cancelled. Attention subjects your flaws and faults to a mob without context.

But much like their namesake, Dark Matter Influencers warp their surroundings. Operate long enough in a market and you’ll inevitably stumble into one. In lieu of 100,000 Instagram followers, the DMI prefers to keep a tight circle of intellectual and entrepreneurial partners. There is no pleasure in impressing strangers.

If I’m right, you’ll see the following play out over the next few years:

- The rich won’t necessarily be the famous. The famous will be “like the rest of us” and not particularly wealthy.

- Our “celebrities” will be increasingly niche as more participants in the traditional influencer economy enter the fray.

- You’ll start to wonder how things are portrayed as getting “worse” by traditional influencers with large audiences while nothing actually changes.

- You will see a growing disconnect between what we are told accumulates wealth and power versus what actually does.

- You’ll see an attention economy become (even more) hyper fractured.

It’s because those that actually can affect change are running up the score quietly. While everyone else is trying to win the game, they are playing for the championship.

Or, to paraphrase author Nassim Taleb, everyone else is trying to win the argument. They are just trying to win.